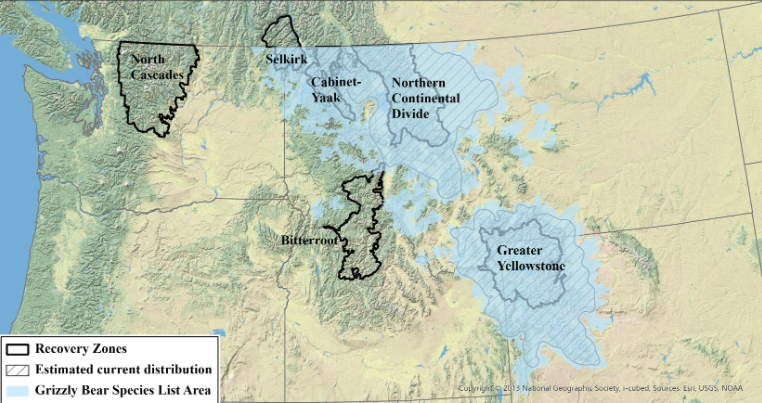

The federal government is once again making plans to reintroduce grizzly bears to Washington’s North Cascade Range. The United States Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Park Service announced in November that they would be initiating an Environmental Impact Statement to begin looking at options for restoring a grizzly population in the Pacific Northwest. They plan to do this by relocating bears from British Columbia and the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem in Northwest Montana.

“This is a first step toward bringing balance back to the ecosystem and restoring a piece of the Pacific Northwest’s natural and cultural heritage,” Don Striker, the superintendent of North Cascades National Park, said in a news release. “With the public’s help, we will evaluate a list of options to determine the best path forward.”

Not surprisingly, the public’s reaction to this announcement has been mixed. Some proponents have drawn comparisons between the North Cascades and the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem, which is home to the largest population of grizzlies in the Lower 48. They point to the national parks and the large amount of habitat that can support a healthy grizzly population. Others argue that while the reintroduction might make ecological sense, there’s also the issue of social tolerance for the apex predators. They bring up the fed’s decision to scrap its North Cascades grizzly reintroduction plans in 2020, which largely failed over pushback from Washingtonians who didn’t want grizzly bears living in their neck of the woods.

But there’s also a third point of view, which is that the fed’s move to reintroduce grizzlies in the North Cascades has less to do with Washington’s grizzly population than it does with existing grizzly bear populations in Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana. Through this more skeptical lens, the reintroduction proposal is seen as a legal chess move that will keep all grizzlies in the Lower 48 on the endangered species list regardless of their success in the northern Rockies.

“We’ve seen this tactic of thwarting effective management for the last 20 years when it comes to wolves and grizzlies,” says Todd Adkins, vice president of governmental affairs for the Sportsmen’s Alliance. “This latest proposal for the North Cascades is clearly just another maneuver to delay responsible, scientific wildlife management of apex predators by state agencies.”

To Adkins’ point, the question of whether grizzlies in the Lower 48 should be taken off the endangered species list has been lobbed back and forth in the courts for years. According to the recovery goals established in the USFWS’ Grizzly Bear Recovery Plan, the grizzly populations in the Greater Yellowstone and Northern Continental Divide Ecosystems are both fully recovered.

The agency’s criteria for GYE grizzly bears calls for a minimum of 500 individuals and at least 48 females with cubs. As of 2021, there were an estimated 1,069 bears, including 84 females with cubs. In terms of available bear habitat in the GYE, the agency explains that all “habitat-based recovery criteria have been maintained since 1998.” The grizzly population in the NCDE is even more robust, with an estimated 1,114 individuals spread across all 23 Bear Management Units as of 2021. That’s compared to the agency’s population benchmark of 800 bears across 21 of those BMU’s.

Following these science-based recovery goals, the USFWS has tried repeatedly since 2005 to de-list grizzly bears. These attempts have been consistently derailed by lawsuits. The most recent attempt to de-list Yellowstone grizzlies was finally quashed in 2020 by a federal judge in San Francisco, who indicated that the USFWS unlawfully delisted the GYE population by failing to consider the effects on all grizzly populations throughout the continental United States.

This decision helps explain why groups like the Sportsmen’s Alliance view the North Cascades reintroduction plan as an attempt to maintain protections for the bears under the Endangered Species Act. They contend that if the feds were to bring grizzlies back to Washington State, the USFWS would need to consider this population when making future management decisions concerning grizzlies in the GYE or NCDE.

“By introducing another grizzly bear population, they’re going to make the legal argument that we can’t de-list either of those two populations (GYE and NCDE) until this population, the North Cascades population, is stable and recovered,” explains Brian Lynn, the vice president of marketing and communications for the Sportsmen’s Alliance.

So, why would the USFWS undermine its own attempts to de-list grizzlies by introducing a new population in Washington? From Lynn’s perspective, it all comes down to changes in political tides and the opposing stances taken by different presidential administrations. He points out that the Trump administration prioritized de-listing grizzlies and returning management of the species to the states, while the Biden administration has not.

Read Next: Martha Williams, the New Director of USFWS, Talks Grizzly Bears, Hunting on Refuges, and the Challenge of Getting More Americans Outdoors

The USFWS, meanwhile, recognizes that the conservation status of a reintroduced grizzly population would be intertwined with the status of the populations already living in the northern Rockies. But the agency contends that the proposed reintroduction could actually expedite the process for de-listing grizzlies in the GYE and NCDE. This is because having more bears on the landscape would bolster the argument that the species has sufficiently recovered.

“Establishing a population of bears in the North Cascades recovery area would contribute positively toward the status of the species, which in turn would be factored into future assessments of the status of grizzly bears in the Lower 48 states,” says USFWS public affairs officer Andrew LaValle.

Regarding those future assessments, the fed’s current proposal considers 200 bears to be a stable and recovered population. This could take anywhere from 60 to 100 years to achieve in the North Cascades Recovery Zone, according to the preliminary EIS scoping document.

As of right now, there are no known grizzlies inhabiting the North Cascades. The last confirmed grizzly sighting in the region was in 1996. There could still be some undetected bears living there, and there are definitely grizzlies living across the border in the Canadian Cascades. (At least one individual has been spotted within 20 miles of the U.S. border during the past five years.) But according to the NPS, this isn’t even close to a viable population, and the agency says it’s very unlikely that Canadian grizzlies could re-populate Washington’s mountains on their own.

What’s even less likely is that all Washingtonians would support the importation of grizzly bears from British Columbia and Montana. As we’ve seen in the ongoing debate surrounding wolf reintroduction in Colorado, there are plenty of urbanites who like the idea of apex predators living wild and free in the mountains. But it’s the rural residents of these states who will have to share the mountains and rangeland with these animals, and many of them have concerns about re-introducing grizzlies there.

Read Next: How Many Wolves Should There Be in Colorado?

“The proposals put forward aren’t asking IF grizzlies should be introduced, but HOW they will be reintroduced,” says Lynn, who lives in Spokane. “They didn’t ask anyone living in the area if they wanted grizzlies reintroduced. They’ve eliminated that option and are only giving scenarios with the end goal of expanding the grizzly population.”

These concerns will likely become more pronounced in the months and years to come. The feds will start drafting an EIS document over the next few months, and they expect to publish the draft by next summer, at which time the public will be allowed to comment. Their final decision on the reintroduction isn’t expected until the summer of 2024.

Dac Collins contributed reporting to this story.